Saddam Hussein

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

(Redirected from

Sadam Husein)

Saddam Hussein Abd al-Majid al-Tikriti (Arabic: صدام حسين عبد المجيد

التكريتي Ṣaddām Ḥusayn ʿAbd al-Majīd al-Tikrītī[1];

28 April 1937[2]

– 30 December 2006)[3]

was the President of Iraq from 16

July 1979 until 9 April 2003.[4][5]

A leading member of the revolutionary Ba'ath

Party, which espoused secular

pan-Arabism,

economic modernization, and Arab socialism, Saddam played a key role in the 1968 coup

that brought the party to long-term power.

As vice president under the ailing General Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr, and at a time when many groups

were considered capable of overthrowing the government, Saddam created

security forces through which he tightly controlled conflict between the

government and the armed forces. In the early 1970s, Saddam spearheaded

Iraq's nationalization of the Western-owned Iraq Petroleum Company, which had long held a

monopoly on the country's oil. Through the 1970s, Saddam cemented his

authority over the apparatuses of government as Iraq's economy grew at a

rapid pace.[6]

As president, Saddam maintained power during the Iran–Iraq War of 1980 through 1988, and

throughout the Persian Gulf War of 1991. During these conflicts,

Saddam suppressed several movements, particularly Shi'a and Kurdish movements seeking to overthrow the government or

gain independence, respectively. Whereas some Arabs venerated him for his aggressive stance

against foreign intervention and for his support for the Palestinians,[7]

other Arabs and Western leaders vilified him as the force behind both a

deadly attack on northern Iraq in 1988 and, two years later, an invasion of Kuwait to the south.

By 2003, the administration of U.S. President George W. Bush perceived

that Saddam remained sufficiently relevant and dangerous to be

overthrown. In March of that year, the U.S. and its allies invaded Iraq, eventually

deposing Saddam. Captured by U.S. forces on 13 December 2003, Saddam was

brought to trial under the Iraqi interim government set up by

U.S.-led forces. On 5 November 2006, he was convicted of charges

related to the 1982 killing of 148 Iraqi Shi'ites convicted of planning an assassination

attempt against him, and was sentenced to death by hanging.

Saddam was executed on 30 December 2006.[8]

By the time of his death, Saddam had become a prolific author.[9][10][11][12]

Among his works are multiple novels dealing with themes

of romance, politics, and war.[13][14][15][16]

Youth

Saddam Hussein Abd al-Majid al-Tikriti was born in the town of Al-Awja,

13 km (8 mi) from the Iraqi town of Tikrit, to

a family of shepherds from the al-Begat tribal

group. His mother, Subha Tulfah al-Mussallat, named her newborn son Saddam, which in Arabic means "One who confronts"; he is always referred to

by this personal name, which may be followed by the

patronymic and other elements. He never knew his father, Hussein 'Abid

al-Majid, who disappeared six months before Saddam was born. Shortly

afterward, Saddam's 13-year-old brother died of cancer.

The infant Saddam was sent to the family of his maternal uncle Khairallah Talfah until he was three.[17]

His mother remarried, and Saddam gained three half-brothers through

this marriage. His stepfather, Ibrahim al-Hassan, treated Saddam harshly

after his return. At around 10 Saddam fled the family and returned to

live in Baghdad

with his uncle Kharaillah Tulfah. Tulfah, the father of Saddam's future

wife, was a devout Sunni Muslim and

a veteran from the 1941 Anglo-Iraqi War between Iraqi

nationalists and the United Kingdom, which remained a major colonial

power in the region.[18]

Later in his life relatives from his native Tikrit became some of his

closest advisors and supporters. Under the guidance of his uncle he

attended a nationalistic high school in Baghdad. After secondary school

Saddam studied at an Iraqi law school for three years, dropping out in

1957 at the age of 20 to join the revolutionary pan-Arab Ba'ath Party,

of which his uncle was a supporter. During this time, Saddam apparently

supported himself as a secondary school teacher.[19]

Revolutionary sentiment was characteristic of the era in Iraq and

throughout the Middle East. In Iraq progressives

and socialists

assailed traditional political elites (colonial era bureaucrats and

landowners, wealthy merchants and tribal chiefs, monarchists).[20]

Moreover, the pan-Arab nationalism of Gamal Abdel Nasser in Egypt

profoundly influenced young Ba'athists like Saddam. The rise of Nasser

foreshadowed a wave of revolutions throughout the Middle East in the

1950s and 1960s, with the collapse of the monarchies of Iraq, Egypt, and Libya.

Nasser inspired nationalists throughout the Middle East by fighting the British

and the French

during the Suez Crisis of 1956, modernizing Egypt, and

uniting the Arab world politically.[21]

In 1958, a year after Saddam had joined the Ba'ath party, army

officers led by General Abd al-Karim Qasim overthrew Faisal II of Iraq. The Ba'athists opposed the new

government, and in 1959 Saddam was involved in the unsuccessful United

States-backed plot to assassinate

Abdul Karim Qassim.[22]

Rise to power

Saddam Hussein after the successful 1963 Ba'ath party coup

Saddam Hussein in Cairo after fleeing there following the failed

assassination attempt against

Qassim

Army officers with ties to the Ba'ath Party overthrew Qassim in a

coup in 1963. Ba'athist leaders were appointed to the cabinet and Abdul Salam Arif became president. Arif dismissed and arrested

the Ba'athist leaders later that year. Saddam returned to Iraq, but was

imprisoned in 1964. Just prior to his imprisonment and until 1968,

Saddam held the position of Ba'ath party secretary.[23]

He escaped from prison in 1967 and quickly became a leading member of

the party. In 1968, Saddam participated in a bloodless coup led by Ahmad Hassan al-Bakr that

overthrew Abdul Rahman Arif. Al-Bakr was named

president and Saddam was named his deputy, and deputy chairman of the

Baathist Revolutionary Command

Council. According to biographers, Saddam never forgot the tensions

within the first Ba'athist government, which formed the basis for his

measures to promote Ba'ath party unity as well as his resolve to

maintain power and programs to ensure social stability.

Saddam Hussein in the past was seen by U.S. intelligence services as a

bulwark of anti-communism in the 1960s and 1970s.[24]

Although Saddam was al-Bakr's deputy, he was a strong behind-the-scenes

party politician. Al-Bakr was the older and more prestigious of the

two, but by 1969 Saddam Hussein clearly had become the moving force

behind the party.

Modernization

program

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, as vice chairman of the

Revolutionary Command Council, formally the al-Bakr's second-in-command,

Saddam built a reputation as a progressive, effective politician.[25]

At this time, Saddam moved up the ranks in the new government by aiding

attempts to strengthen and unify the Ba'ath party and taking a leading

role in addressing the country's major domestic problems and expanding

the party's following.

After the Baathists took power in 1968, Saddam focused on attaining

stability in a nation riddled with profound tensions. Long before

Saddam, Iraq had been split along social, ethnic, religious, and

economic fault lines: Sunni versus Shi'ite, Arab versus Kurd, tribal chief versus urban merchant, nomad

versus peasant.[26]

Stable rule in a country rife with factionalism required both massive repression

and the improvement of living standards.[26]

Saddam actively fostered the modernization of the Iraqi economy along

with the creation of a strong security apparatus to prevent coups

within the power structure and insurrections apart from it. Ever

concerned with broadening his base of support among the diverse elements

of Iraqi society and mobilizing mass support, he closely followed the

administration of state welfare and development programs.

At the center of this strategy was Iraq's oil. On 1 June 1972, Saddam

oversaw the seizure of international oil interests, which, at the time,

dominated the country's oil sector. A year later, world oil prices rose

dramatically as a result of the 1973 energy crisis, and

skyrocketing revenues enabled Saddam to expand his agenda.

Within just a few years, Iraq was providing social services that were

unprecedented among Middle Eastern countries. Saddam established and

controlled the "National Campaign for the Eradication of Illiteracy" and

the campaign for "Compulsory Free Education in Iraq," and largely under

his auspices, the government established universal free schooling up to

the highest education levels; hundreds of thousands learned to read in

the years following the initiation of the program. The government also

supported families of soldiers, granted free hospitalization to

everyone, and gave subsidies to farmers. Iraq created one of the most

modernized public-health systems in the Middle East, earning Saddam an

award from the United Nations Educational, Scientific

and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).[27][28]

To diversify the largely oil-based Iraqi economy, Saddam implemented a national infrastructure

campaign that made great progress in building roads, promoting mining,

and developing other industries. The campaign revolutionized Iraq's

energy industries. Electricity was brought to nearly every city in Iraq,

and many outlying areas.

Before the 1970s, most of Iraq's people lived in the countryside,

where Saddam himself was born and raised, and roughly two-thirds were

peasants. This number would decrease quickly during the 1970s as the

country invested much of its oil profits into industrial expansion.

Nevertheless, Saddam focused on fostering loyalty to the Ba'athist

government in the rural areas. After nationalizing foreign oil

interests, Saddam supervised the modernization of the countryside,

mechanizing agriculture on a large scale, and distributing

land to peasant farmers.[19]

The Ba'athists established farm cooperatives,

in which profits were distributed according to the labors of the

individual and the unskilled were trained. The government also doubled

expenditures for agricultural development in 1974–1975. Moreover, agrarian reform in Iraq improved the living standard of the peasantry and increased production.

Saddam became personally associated with Ba'athist welfare

and economic development programs in the

eyes of many Iraqis, widening his appeal both within his traditional

base and among new sectors of the population. These programs were part

of a combination of "carrot and stick" tactics to enhance support in the working

class, the peasantry, and within the party and the government

bureaucracy.

Saddam's organizational prowess was credited with Iraq's rapid pace

of development in the 1970s; development went forward at such a fevered

pitch that two million people from other Arab countries and even Yugoslavia worked

in Iraq to meet the growing demand for labor.

Succession

In 1976, Saddam rose to the position of general in the Iraqi armed

forces, and rapidly became the strongman of the government. As the

ailing, elderly al-Bakr became unable to execute his duties, Saddam took

on an increasingly prominent role as the face of the government both

internally and externally. He soon became the architect of Iraq's

foreign policy and represented the nation in all diplomatic situations.

He was the de facto leader of Iraq some years before he formally

came to power in 1979. He slowly began to consolidate his power over

Iraq's government and the Ba'ath party. Relationships with fellow party

members were carefully cultivated, and Saddam soon accumulated a

powerful circle of support within the party.

In 1979 al-Bakr started to make treaties with Syria, also

under Ba'athist leadership, that would lead to unification between the

two countries. Syrian President Hafez al-Assad would become deputy leader in a union, and

this would drive Saddam to obscurity. Saddam acted to secure his grip on

power. He forced the ailing al-Bakr to resign on 16 July 1979, and

formally assumed the presidency.

Shortly afterwards, he convened an assembly of Ba'ath party leaders

on 22 July 1979. During the assembly, which he ordered videotaped (see [29]),

Saddam claimed to have found a fifth

column within the Ba'ath Party and directed Muhyi Abdel-Hussein to

read out a confession and the names of 68 alleged co-conspirators. These

members were labelled "disloyal" and were removed from the room one by

one and taken into custody. After the list was read, Saddam

congratulated those still seated in the room for their past and future

loyalty. The 68 people arrested at the meeting were subsequently tried

together and found guilty of treason.

22 were sentenced to execution. Other high-ranking members of the party

formed the firing squad. By 1 August 1979, hundreds of high-ranking

Ba'ath party members had been executed.[30][31]

Secular leadership

To the consternation of Islamic conservatives,

Saddam's government gave women added freedoms and offered them

high-level government and industry jobs. Saddam also created a

Western-style legal system, making Iraq the only country in the Persian

Gulf region not ruled according to traditional Islamic law (Sharia).

Saddam abolished the Sharia courts, except for personal injury claims.

Domestic conflict impeded Saddam's modernizing projects. Iraqi

society is divided along lines of language, religion and ethnicity;

Saddam's government rested on the support of the 20% minority of largely

working class, peasant, and lower middle

class Sunnis, continuing a pattern that dates back at least to the

British colonial authority's reliance on them as administrators.

The Shi'a majority were long a source of opposition to the

government's secular policies, and the Ba'ath Party was increasingly

concerned about potential Shi'a Islamist influence following the Iranian Revolution of 1979. The Kurds of northern Iraq (who are Sunni but not Arabs) were

also permanently hostile to the Ba'athist party's pan-Arabism. To

maintain power Saddam tended either to provide them with benefits so as

to co-opt them into the regime, or to take repressive measures against

them. The major instruments for accomplishing this control were the paramilitary

and police

organizations. Beginning in 1974, Taha Yassin Ramadan, a close associate of Saddam,

commanded the People's Army, which was responsible for internal

security. As the Ba'ath Party's paramilitary, the People's Army acted as

a counterweight against any coup attempts by the regular armed forces.

In addition to the People's Army, the Department of General Intelligence

(Mukhabarat) was the most

notorious arm of the state security system, feared for its use of torture

and assassination. It was commanded by Barzan Ibrahim al-Tikriti,

Saddam's younger half-brother. Since 1982, foreign observers believed

that this department operated both at home and abroad in their mission

to seek out and eliminate Saddam's perceived opponents.[32]

Saddam justified Iraqi nationalism

by claiming a unique role of Iraq in the history of the Arab world. As

president, Saddam made frequent references to the Abbasid period, when Baghdad was the political,

cultural, and economic capital of the Arab world. He also

promoted Iraq's pre-Islamic role as Mesopotamia,

the ancient cradle of civilization,

alluding to such historical figures as Nebuchadnezzar II and Hammurabi.

He devoted resources to archaeological explorations. In effect, Saddam

sought to combine pan-Arabism and Iraqi nationalism, by promoting the

vision of an Arab world united and led by Iraq.

As a sign of his consolidation of power, Saddam's personality cult pervaded Iraqi society.

Thousands of portraits, posters, statues and murals were erected in his

honor all over Iraq. His face could be seen on the sides of office

buildings, schools, airports, and shops, as well as on Iraqi currency.

Saddam's personality cult reflected his efforts to appeal to the various

elements in Iraqi society. He appeared in the costumes of the Bedouin,

the traditional clothes of the Iraqi peasant (which he essentially wore

during his childhood), and even Kurdish clothing, but also appeared in Western suits,

projecting the image of an urbane and modern leader. Sometimes he would

also be portrayed as a devout Muslim, wearing full headdress and robe,

praying toward Mecca.

Foreign affairs

Donald Rumsfeld, at the time

Ronald

Reagan's special envoy to the

Middle

East, meeting Saddam Hussein on 19-20 December 1983. During the

1980s, the United States maintained cordial relations with Saddam as a

bulwark against Iran.

In foreign affairs, Saddam sought to have Iraq play a leading role in

the Middle East. Iraq signed an aid pact with the Soviet Union in 1972,

and arms were sent along with several thousand advisers. However, the

1978 crackdown on Iraqi Communists

and a shift of trade toward the West strained Iraqi relations with the

Soviet Union; Iraq then took on a more Western orientation until the Persian

Gulf War in 1991.[33]

After the oil crisis of 1973, France had changed to a

more pro-Arab policy and was accordingly rewarded by Saddam with closer

ties. He made a state visit to France in 1976, cementing close ties with

some French business and ruling political circles. In 1975 Saddam

negotiated an accord with Iran that contained Iraqi concessions on

border disputes. In return, Iran agreed to stop supporting opposition

Kurds in Iraq. Saddam led Arab opposition to the Camp David Accords between Egypt and Israel (1979).

Saddam initiated Iraq's nuclear enrichment project in the 1980s, with

French assistance. The first Iraqi nuclear reactor was named by the

French Osirak.

Osirak was destroyed on 7 June 1981[34]

by an Israeli

air strike (Operation Opera).

Nearly from its founding as a modern state in 1920, Iraq has had to

deal with Kurdish separatists in the northern part of the country.

(Humphreys, 120) Saddam did negotiate an agreement in 1970 with

separatist Kurdish leaders, giving them autonomy, but the agreement

broke down. The result was brutal fighting between the government and

Kurdish groups and even Iraqi bombing of Kurdish villages in Iran, which

caused Iraqi relations with Iran to deteriorate. However, after Saddam

had negotiated the 1975 treaty with Iran, the Shah withdrew support for

the Kurds, who suffered a total defeat.

Iran–Iraq War

Main article:

Iran–Iraq WarIn 1979 Iran's Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi was overthrown

by the Islamic Revolution, thus giving way to an

Islamic republic led by the Ayatollah Khomeini. The influence of revolutionary Shi'ite

Islam grew apace in the region, particularly in countries with large

Shi'ite populations, especially Iraq. Saddam feared that radical Islamic

ideas—hostile to his secular rule—were rapidly spreading inside his

country among the majority Shi'ite population.

There had also been bitter enmity between Saddam and Khomeini since

the 1970s. Khomeini, having been exiled from

Iran in 1964, took up residence in Iraq, at the Shi'ite holy city of An Najaf. There he involved himself with Iraqi

Shi'ites and developed a strong, worldwide religious and political

following against the Iranian Government, whom Saddam tolerated.

However, when Khomeini began to urge the Shi'ites there to overthrow

Saddam and under pressure from the Shah, who had agreed to a

rapprochement between Iraq and Iran in 1975, Saddam agreed to expel

Khomeini in 1978 to France. However this turned out to be an imminent

failure and a political catalyst, for Khomeini had access to more media

connections and also collaborated with a much larger Iranian community

under his support whom he used to his advantage.

After Khomeini gained power, skirmishes between Iraq and

revolutionary Iran occurred for ten months over the sovereignty of the

disputed Shatt al-Arab waterway, which divides the two

countries. During this period, Saddam Hussein publicly maintained that

it was in Iraq's interest not to engage with Iran, and that it was in

the interests of both nations to maintain peaceful relations. However,

in a private meeting with Salah Omar Al-Ali, Iraq's permanent ambassador to the United Nations, he revealed that he intended to invade

and occupy a large part of Iran within months. Iraq invaded Iran, first

attacking Mehrabad Airport of Tehran and

then entering the oil-rich Iranian land of Khuzestan, which also has a sizable

Arab minority, on 22 September 1980 and declared it a new province

of Iraq. With the support of the Arab states, the United States, the

Soviet Union, and Europe, and heavily financed by the Arab states of the

Persian Gulf, Saddam Hussein had become "the defender of the Arab

world" against a revolutionary Iran. Consequently, many viewed Iraq as

"an agent of the civilized world".[35]

The blatant disregard of international law and violations of

international borders were ignored. Instead Iraq received economic and

military support from its allies, who conveniently overlooked Saddam's

use of chemical warfare against the Kurds and the Iranians and Iraq's

efforts to develop nuclear weapons.[35]

In the first days of the war, there was heavy ground fighting around

strategic ports as Iraq launched an attack on Khuzestan. After making

some initial gains, Iraq's troops began to suffer losses from human wave attacks by Iran. By 1982, Iraq was on

the defensive and looking for ways to end the war.

At this point, Saddam asked his ministers for candid advice. Health Minister Dr Riyadh

Ibrahim suggested that Saddam temporarily step down to promote peace

negotiations. Initially, Saddam Hussein appeared to take in this

opinion as part of his cabinet democracy. A few weeks later, Dr Ibrahim

was sacked when held responsible for a fatal incident in an Iraqi

hospital where a patient died from intravenous administration of the

wrong concentration of Potassium supplement.

Dr Ibrahim was arrested a few days after he started his new life as a

sacked Minister. He was known to have publicly declared before that

arrest that he was "glad that he got away alive." Pieces of Ibrahim's

dismembered body were delivered to his wife the next day.[36]

Iraq quickly found itself bogged down in one of the longest and most

destructive wars of attrition of the twentieth

century. During the war, Iraq used chemical weapons against Iranian forces

fighting on the southern front and Kurdish separatists who were

attempting to open up a northern front in Iraq with the help of Iran.

These chemical weapons were developed by Iraq from materials and

technology supplied primarily by West

German companies.[37]

Saddam reached out to other Arab governments for cash and political

support during the war, particularly after Iraq's oil industry severely

suffered at the hands of the Iranian navy in the Persian

Gulf. Iraq successfully gained some military and financial aid, as

well as diplomatic and moral support, from the Soviet Union, China,

France, and the United States, which together feared the prospects of

the expansion of revolutionary Iran's influence in the region. The

Iranians, demanding that the international community should force Iraq

to pay war reparations to Iran, refused any suggestions for a

cease-fire. Despite several calls for a ceasefire by the United Nations Security Council,

hostilities continued until 20 August 1988.

On 16 March 1988, the Kurdish town of Halabja

was attacked with a mix of mustard gas and nerve

agents, killing 5,000 civilians, and maiming, disfiguring, or

seriously debilitating 10,000 more. (see Halabja poison gas attack)[38]

The attack occurred in conjunction with the 1988 al-Anfal campaign designed to reassert

central control of the mostly Kurdish population of areas of northern

Iraq and defeat the Kurdish peshmerga rebel forces. The United States now

maintains that Saddam ordered the attack to terrorize the Kurdish

population in northern Iraq,[38]

but Saddam's regime claimed at the time that Iran was responsible for

the attack[39]

and US analysts supported the claim until several

years later.

The bloody eight-year war ended in a stalemate. There were hundreds

of thousands of casualties with estimates of up to one million dead.

Neither side had achieved what they had originally desired and at the

borders were left nearly unchanged. The southern, oil rich and

prosperous Khuzestan and Basra area (the main focus of the war, and the

primary source of their economies) were almost completely destroyed and

were left at the pre 1979 border, while Iran managed to make some small

gains on its borders in the Northern Kurdish area. Both economies,

previously healthy and expanding, were left in ruins.

Borrowing money from the U.S. was making Iraq dependent on outside

loans, embarrassing a leader who had sought to define Arab nationalism.

Saddam also borrowed a tremendous amount of money from other Arab states

during the 1980s to fight Iran, mainly to prevent the expansion of

Shiite radicalism. However, this had proven to completely backfire both

on Iraq and on the part of the Arab states, for Khomeini was praised as a

hero for managing to defend Iran and maintain the war with little

foreign support against the heavily backed Iraq, and only managed to

boost Islamic radicalism in the Arab states. Faced with rebuilding

Iraq's infrastructure, Saddam desperately sought out cash once again,

this time for postwar reconstruction.

Tensions with

Kuwait

The end of the war with Iran served to deepen latent tensions between

Iraq and its wealthy neighbor Kuwait.

Saddam urged the Kuwaitis to forgive the Iraqi debt accumulated in the

war, some $30 billion, but they refused.[40]

Saddam pushed oil-exporting countries to raise oil prices by cutting

back production; Kuwait refused, however. In addition to refusing the

request, Kuwait spearheaded the opposition in OPEC to the

cuts that Saddam had requested. Kuwait was pumping large amounts of oil,

and thus keeping prices low, when Iraq needed to sell high-priced oil

from its wells to pay off a huge debt.

Saddam had always argued that Kuwait was historically an integral

part of Iraq, and that Kuwait had only come into being through the

maneuverings of British imperialism; this echoed a belief that Iraqi

nationalists had voiced for the past 50 years. This belief was one of

the few articles of faith uniting the political scene in a nation rife

with sharp social, ethnic, religious, and ideological divides.[40]

The extent of Kuwaiti oil reserves also intensified tensions in the

region. The oil reserves of Kuwait (with a population of 2 million next

to Iraq's 25) were roughly equal to those of Iraq. Taken together, Iraq

and Kuwait sat on top of some 20 percent of the world's known oil

reserves; as an article of comparison, Saudi

Arabia holds 25 percent.[40]

Saddam complained to the U.S. State Department that the

Kuwaiti

monarchy had slant drilled oil out of wells that Iraq considered to

be within its disputed border with Kuwait. Saddam still had an

experienced and well-equipped army, which he used to influence regional

affairs. He later ordered troops to the Iraq–Kuwait border.

As Iraq-Kuwait relations rapidly deteriorated, Saddam was receiving

conflicting information about how the U.S. would respond to the

prospects of an invasion. For one, Washington had been taking measures

to cultivate a constructive relationship with Iraq for roughly a decade.

The Reagan administration gave Saddam roughly $40 billion in aid

in the 1980s to fight Iran, nearly all of it on credit. The U.S. also

gave Saddam billions of dollars to keep him from forming a strong

alliance with the Soviets.[41]

Saddam's Iraq became "the third-largest recipient of US assistance".[42]

U.S. ambassador to Iraq April

Glaspie met with Saddam in an emergency meeting on 25 July, where

the Iraqi leader stated his intention to give negotiations only.. one

more brief chance before forcing Iraq's claims on Kuwait.[43]

U.S. officials attempted to maintain a conciliatory line with Iraq,

indicating that while George H. W. Bush and James

Baker did not want force used, they would not take any position on

the Iraq–Kuwait boundary dispute and did not want to become involved.[44]

Whatever Glapsie did or did not say in her interview with Saddam, the

Iraqis assumed that the United States had invested too much in building

relations with Iraq over the 1980s to sacrifice them for Kuwait.[45]

Later, Iraq and Kuwait met for a final negotiation session, which

failed. Saddam then sent his troops into Kuwait. As tensions between

Washington and Saddam began to escalate, the Soviet

Union, under Mikhail Gorbachev, strengthened its military relationship

with the Iraqi leader, providing him military advisers, arms and aid.[46]

Gulf War

On 2 August 1990, Saddam invaded and annexed Kuwait, thus sparking an

international crisis. Just two years after the 1988 Iraq and Iran

truce, "Saddam Hussein did what his Gulf patrons had earlier paid him to

prevent." Having removed the threat of Iranian fundamentalism he

"overran Kuwait and confronted his Gulf neighbors in the name of Arab

nationalism and Islam."[35]

The U.S. had provided assistance to Saddam Hussein in the war with

Iran, but with Iraq's seizure of the oil-rich emirate of Kuwait in

August 1990 the United States led a United Nations coalition that drove Iraq's troops from

Kuwait in February 1991. The ability for Saddam Hussein to pursue such

military aggression was from a "military machine paid for in large part

by the tens of billions of dollars Kuwait and the Gulf states had poured

into Iraq and the weapons and technology provided by the Soviet Union,

Germany, and France."[35]

U.S. President George H. W. Bush responded cautiously for the first

several days. On one hand, Kuwait, prior to this point, had been a

virulent enemy of Israel and was the Persian Gulf monarchy that had had

the most friendly relations with the Soviets.[47]

On the other hand, Washington foreign policymakers, along with Middle

East experts, military critics, and firms heavily invested in the

region, were extremely concerned with stability in this region.[48]

The invasion immediately triggered fears that the world's price of oil, and therefore control of the world

economy, was at stake. Britain profited heavily from billions of

dollars of Kuwaiti investments and bank deposits. Bush was perhaps

swayed while meeting with British prime minister Margaret Thatcher, who happened to be in the U.S. at the

time.[49]

Co-operation between the United States and the Soviet Union made

possible the passage of resolutions in the United Nations Security Council

giving Iraq a deadline to leave Kuwait and approving the use of force

if Saddam did not comply with the timetable. U.S. officials feared Iraqi

retaliation against oil-rich Saudi

Arabia, since the 1940s a close ally of Washington, for the Saudis'

opposition to the invasion of Kuwait. Accordingly, the U.S. and a group

of allies, including countries as diverse as Egypt, Syria and Czechoslovakia, deployed a massive amount of

troops along the Saudi border with Kuwait and Iraq in order to encircle

the Iraqi army, the largest in the Middle East.

During the period of negotiations and threats following the invasion,

Saddam focused renewed attention on the Palestinian

problem by promising to withdraw his forces from Kuwait if Israel

would relinquish the occupied territories in the West

Bank, the Golan Heights, and the Gaza

Strip. Saddam's proposal further split the Arab world, pitting U.S.-

and Western-supported Arab states against the Palestinians. The allies

ultimately rejected any linkage between the Kuwait crisis and

Palestinian issues.

Saddam ignored the Security Council deadline. Backed by the Security

Council, a U.S.-led coalition launched round-the-clock missile and

aerial attacks on Iraq, beginning 16 January 1991. Israel, though

subjected to attack by Iraqi missiles, refrained from retaliating in

order not to provoke Arab states into leaving the coalition. A ground

force comprised largely of U.S. and British armoured and infantry

divisions ejected Saddam's army from Kuwait in February 1991 and

occupied the southern portion of Iraq as far as the Euphrates.

On 6 March 1991, Bush announced:

| “ |

What is at stake is more

than one small country, it is a big idea — a new world order, where diverse

nations are drawn together in common cause to achieve the universal

aspirations of mankind: peace and security, freedom, and the rule of

law. |

” |

In the end, the over-manned and under-equipped Iraqi army proved

unable to compete on the battlefield with the highly mobile coalition

land forces and their overpowering air support. Some 175,000 Iraqis were

taken prisoner and casualties were estimated at over 85,000. As part of

the cease-fire agreement, Iraq agreed to scrap all poison gas and germ weapons and allow UN observers to inspect the sites.

UN trade sanctions would remain in effect until Iraq complied with all

terms. Saddam publicly claimed victory at the end of the war.

Postwar period

Iraq's ethnic and religious divisions, together with the brutality of

the conflict that this had engendered, laid the groundwork for postwar

rebellions. In the aftermath of the fighting, social and ethnic unrest

among Shi'ite Muslims, Kurds, and dissident military units threatened

the stability of Saddam's government. Uprisings erupted in the Kurdish

north and Shi'a southern and central parts of Iraq, but were ruthlessly

repressed.

The United States, which had urged Iraqis to rise up against Saddam,

did nothing to assist the rebellions. The Iranians, who had earlier

called for the overthrow of Saddam, were in no state to even intervene

on behalf of the rebellions due to the disastrous state of its economy

and military. Turkey opposed any prospect of Kurdish independence,

and the Saudis and other conservative Arab states feared an Iran-style

Shi'ite revolution. Saddam, having survived the immediate crisis in the

wake of defeat, was left firmly in control of Iraq, although the country

never recovered either economically or militarily from the Gulf War.

Saddam routinely cited his survival as "proof" that Iraq had in fact won

the war against the U.S. This message earned Saddam a great deal of

popularity in many sectors of the Arab world. John Esposito, however,

claims that "Arabs and Muslims were pulled in two directions. That they

rallied not so much to Saddam Hussein as to the bipolar nature of the

confrontation (the West versus the Arab Muslim world) and the issues

that Saddam proclaimed: Arab unity, self-sufficiency, and social

justice." As a result, Saddam Hussein appealed to many people for the

same reasons that attracted more and more followers to Islamic

revivalism and also for the same reasons that fueled anti-Western

feelings. "As one U.S. Muslim observer noted: People forgot about

Saddam's record and concentrated on America...Saddam Hussein might be

wrong, but it is not America who should correct him." A shift was,

therefore, clearly visible among many Islamic movements in the post war

period "from an initial Islamic ideological rejection of Saddam Hussein,

the secular persecutor of Islamic movements, and his invasion of Kuwait

to a more populist Arab nationalist,

anti-imperialist support for Saddam (or more precisely those issues he

represented or championed) and the condemnation of foreign intervention

and occupation."[35]

Saddam, therefore, increasingly portrayed himself as a devout Muslim, in

an effort to co-opt the conservative religious segments of society.

Some elements of Sharia law were re-introduced, and the ritual phrase "Allahu Akbar" ("God is great"), in Saddam's

handwriting, was added to the national flag.

Relations between the United States and Iraq remained tense following

the Gulf War. The U.S. launched a missile attack aimed at Iraq's

intelligence headquarters in Baghdad

26 June 1993, citing evidence of repeated Iraqi violations of the "no

fly zones" imposed after the Gulf War and for incursions into Kuwait.

The UN sanctions placed upon Iraq when it invaded Kuwait were not

lifted, blocking Iraqi oil exports. This caused immense hardship in Iraq

and virtually destroyed the Iraqi economy and state infrastructure.

Only smuggling across the Syrian border, and humanitarian aid ameliorated the

humanitarian crisis.[50]

On 9 December 1996 the United Nations allowed Saddam's government to begin selling

limited amounts of oil for food and medicine. Limited amounts of income

from the United Nations started flowing into Iraq through the UN Oil for Food program.

U.S. officials continued to accuse Saddam of violating the terms of

the Gulf War's cease fire, by developing weapons of mass

destruction and other banned weaponry, and violating the UN-imposed

sanctions and "no-fly zones." Isolated military strikes by U.S. and

British forces continued on Iraq sporadically, the largest being Operation Desert Fox

in 1998. Western charges of Iraqi resistance to UN access to suspected

weapons were the pretext for crises between 1997 and 1998, culminating

in intensive U.S. and British missile strikes on Iraq, 16-19 December

1998. After two years of intermittent activity, U.S. and British

warplanes struck harder at sites near Baghdad in February 2001.

Saddam's support base of Tikriti tribesmen, family members, and other

supporters was divided after the war, and in the following years,

contributing to the government's increasingly repressive and arbitrary

nature. Domestic repression inside Iraq grew worse, and Saddam's sons, Uday

and Qusay Hussein, became increasingly powerful and carried out

a private reign of terror.

Iraqi co-operation with UN weapons inspection teams was intermittent

throughout the 1990s.

2003 invasion

of Iraq

Satellite channels

broadcasting the besieged Iraqi leader among cheering crowds as U.S.-led

troops push toward the capital city.

[51]

4 April 2003.

The U.S. continued to view Saddam as a bellicose tyrant who was a

threat to the stability of the region. During the 1990s, President Bill

Clinton maintained sanctions and ordered air strikes in the "Iraqi

no-fly zones" (Operation Desert Fox), in

the hope that Saddam would be overthrown by political enemies inside

Iraq.

The domestic political equation changed in the U.S. after the September 11,

2001 attacks; in his January 2002 state of the union address to

Congress, President George W. Bush spoke of an "axis

of evil" consisting of Iran, North

Korea, and Iraq.

Moreover, Bush announced that he would possibly take action to topple

the Iraqi government, because of the alleged threat of its "weapons of mass

destruction." Bush claimed, "The Iraqi regime has plotted to develop

anthrax,

and nerve gas, and nuclear weapons for over a decade...

Iraq continues to flaunt its hostility toward America and to support

terror."[52][53]

Saddam Hussein claimed that he falsely led the world to believe Iraq

possessed nuclear weapons in order to appear strong against Iran.[54]

With war looming on 24 February 2003, Saddam Hussein talked with CBS News

reporter Dan Rather for more than three hours, his first interview

with a U.S. reporter in over a decade.[55]

CBS aired the taped interview later that week.

The Iraqi government and military collapsed within three weeks of the

beginning of the U.S.-led 2003 invasion of Iraq on 20 March. The United

States made at least two attempts to kill Saddam with targeted air

strikes, but both failed to hit their target, killing civilians instead.

By the beginning of April, U.S.-led forces occupied much of Iraq. The

resistance of the much-weakened Iraqi Army either crumbled or shifted to

guerrilla tactics, and it appeared that Saddam

had lost control of Iraq. He was last seen in a video which purported to

show him in the Baghdad suburbs surrounded by supporters. When Baghdad

fell to U.S-led forces on 9 April, Saddam was nowhere to be found.

Incarceration

and trial

Capture and

incarceration

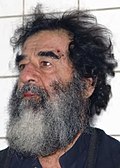

|

|

|

Saddam shortly after capture by American forces, and after being shaved

to confirm his identity |

In April 2003, Saddam's whereabouts remained in question during the

weeks following the fall of Baghdad and the conclusion of the major

fighting of the war. Various sightings of Saddam were reported in the

weeks following the war but none was authenticated. At various times

Saddam released audio tapes promoting popular resistance to the U.S.-led

occupation.

Saddam was placed at the top of the U.S. list of "most-wanted Iraqis." In July

2003, his sons Uday and Qusay and 14-year-old grandson Mustapha were killed in a three-hour[56]

gunfight with U.S. forces.

On 14 December 2003, U.S. administrator in Iraq L. Paul Bremer announced that Saddam Hussein had been

captured at a farmhouse in ad-Dawr

near Tikrit.[57]

Bremer presented video footage of Saddam in custody.

Saddam was shown with a full beard and hair longer than his familiar

appearance. He was described by U.S. officials as being in good health.

Bremer reported plans to put Saddam on trial, but claimed that the

details of such a trial had not yet been determined. Iraqis and

Americans who spoke with Saddam after his capture generally reported

that he remained self-assured, describing himself as a "firm but just

leader."

According to U.S. military sources, following his capture by U.S.

forces on 13 December Saddam was transported to a U.S. base near Tikrit,

and later taken to the U.S. base near Baghdad. The day after his

capture he was reportedly visited by longtime opponents such as Ahmed

Chalabi.

British tabloid newspaper The Sun posted a picture of Saddam wearing

white briefs on the front cover of a newspaper. Other photographs inside

the paper show Saddam washing his trousers, shuffling, and sleeping.

The United States

Government stated that it considers the release of the pictures a

violation of the Geneva Convention, and that it would

investigate the photographs.[58][59]

During this period Hussein was interrogated by

FBI agent George Piro.[60]

The guards at the Baghdad detention facility called their prisoner

"Vic," and let him plant a little garden near his cell. The nickname and

the garden are among the details about the former Iraqi leader that

emerged during a 27 March 2008 tour of prison of the Baghdad

cell where Saddam slept, bathed, and kept a journal in the final days

before his execution.[61]

Trial

Saddam speaking at a pre-trial hearing.

On 30 June 2004, Saddam Hussein, held in custody by U.S. forces at

the U.S. base "Camp Cropper," along with 11 other senior

Baathist leaders, were handed over legally (though not physically) to

the interim Iraqi government to stand trial for crimes against

humanity and other offences.

A few weeks later, he was charged by the Iraqi Special Tribunal with

crimes committed against residents of Dujail in

1982, following a failed assassination attempt against him. Specific

charges included the murder of 148 people, torture

of women and children and the illegal arrest of 399 others.[62][63]

Among the many challenges of the trial were:

- Saddam and his lawyers' contesting the court's authority and

maintaining that he was still the President of Iraq.[64]

- The assassinations and attempts on the lives of several of Saddam's

lawyers.

- Midway through the trial, the chief presiding judge was replaced.

On 5 November 2006, Saddam Hussein was found guilty of crimes against

humanity and sentenced to death by hanging.

Saddam's half brother, Barzan Ibrahim, and Awad Hamed al-Bandar, head of Iraq's Revolutionary

Court in 1982, were convicted of similar charges. The verdict and

sentencing were both appealed but subsequently affirmed by Iraq's Supreme

Court of Appeals.[65]

On 30 December 2006, Saddam was hanged.[8]

Execution

Saddam was hanged on the first day of Eid

ul-Adha, 30 December 2006, despite his wish to be shot (which he

felt would be more dignified).[66]

The execution was carried out at Camp

Justice, an Iraqi army base in Kadhimiya,

a neighborhood of northeast Baghdad.

The execution was videotaped on a mobile

phone and he and his captors could be heard insulting each other.

The video was leaked to electronic media and posted on the Internet

within hours, becoming the subject of global controversy.[67]

It was later claimed by the head guard at the tomb where his body

remains that Saddam's body was stabbed six times after the execution.[68]

Not long before the execution, Saddam's lawyers released his last

letter. The following includes several excerpts:

| “ |

To the great nation, to the

people of our country, and humanity,

Many of you have known the writer of this letter to be faithful,

honest, caring for others, wise, of sound judgment, just, decisive,

careful with the wealth of the people and the state ... and that his

heart is big enough to embrace all without discrimination.

You have known your brother and leader very well and he never bowed

to the despots and, in accordance with the wishes of those who loved

him, remained a sword and a banner.

This is how you want your brother, son or leader to be ... and those

who will lead you (in the future) should have the same qualifications.

Here, I offer my soul to God as a sacrifice, and if He wants, He will

send it to heaven with the martyrs, or, He will postpone that ... so

let us be patient and depend on Him against the unjust nations.

Remember that God has enabled you to become an example of love,

forgiveness and brotherly coexistence ... I call on you not to hate

because hate does not leave a space for a person to be fair and it makes

you blind and closes all doors of thinking and keeps away one from

balanced thinking and making the right choice.

I also call on you not to hate the peoples of the other countries

that attacked us and differentiate between the decision-makers and

peoples. Anyone who repents - whether in Iraq or abroad - you must

forgive him.

You should know that among the aggressors, there are people who

support your struggle against the invaders, and some of them volunteered

for the legal defence of prisoners, including Saddam Hussein ... some

of these people wept profusely when they said goodbye to me.

Dear faithful people, I say goodbye to you, but I will be with the

merciful God who helps those who take refuge in him and who will never

disappoint any faithful, honest believer ... God is Great ... God is

great ... Long live our nation ... Long live our great struggling people

... Long live Iraq, long live Iraq ... Long live Palestine ... Long

live jihad and the mujahedeen (the insurgency).

Saddam Hussein President and Commander in Chief of the Iraqi Mujahed

Armed Forces

Additional clarification note:

I have written this letter because the lawyers told me that the

so-called criminal court — established and named by the invaders — will

allow the so-called defendants the chance for a last word. But that

court and its chief judge did not give us the chance to say a word, and

issued its verdict without explanation and read out the sentence —

dictated by the invaders — without presenting the evidence. I wanted the

people to know this.[69]

|

” |

| |

— Letter by Saddam Hussein

|

A second unofficial video, apparently showing Saddam's body on a

trolley, emerged several days later. It sparked speculation that the

execution was carried out incorrectly as Saddam Hussein had a gaping

hole in his neck.[70]

Saddam was buried at his birthplace of Al-Awja

in Tikrit, Iraq, 3 km (2 mi) from his sons Uday

and Qusay Hussein, on 31 December 2006.[71]

Marriage

and family relationships

Saddam Hussein's family (clockwise from top L), son-in-law Saddam Kamel

and daughter Rana, son Qusay and daughter-in-law Sahar, daughter Raghad

and son-in-law Hussein Kamal, son Uday, daughter Hala, Saddam Hussein

and his first wife Sajda Talfah, pose in this undated photo from the

private archive of an official photographer for the regime

While Saddam has no official marital history he is believed to have

been married to at least four women, two of whom have been confirmed as

his wives, and had five children.[citation needed]

- Saddam married his first wife and cousin Sajida

Talfah (or Tulfah/Tilfah) [72]

in 1958 [73]

in an arranged marriage. Sajida is the daughter of Khairallah Talfah,

Saddam's uncle and mentor. Their marriage was arranged for Hussein at

age five when Sajida was seven; however, the two never met until their

wedding. They were married in Egypt during

his exile. The couple had five children.]],[74]

-

- Uday Hussein (18 June 1964 - 22 July 2003), was Saddam's

oldest son, who ran the Iraqi Football

Association, Fedayeen Saddam, and several media

corporations in Iraq including Iraqi TV and the newspaper Babel. Uday, while Saddam's favorite son and raised

to succeed him, eventually fell out of favour with his father due to

his erratic behavior; he was responsible for many car crashes and rapes around

Baghdad, constant feuds with other members his family, and killing his

father's favorite valet and food taster Kamel Hana Gegeo at a party in Egypt honoring Egyptian first

lady Suzanne Mubarak. He was widely known for his

paranoia and his obsession with torturing people who disappointed him

in any way, which included tardy girlfriends, friends who disagreed with

him and, most notoriously, Iraqi athletes who performed poorly. He was

briefly married to Izzat Ibrahim ad-Douri's daughter but later

divorced her. The couple had no children. He was killed in a gun battle

with US Forces in Mosul.[citation needed]

- Qusay Hussein (17 May 1966 - 22 July 2003), was Saddam's

second — and, after the mid-1990s, his favorite — son. Qusay was

believed to have been Saddam's later intended successor as he was less

erratic than his older brother and kept a low profile. He was second in

command of the military (behind his father) and ran the elite Iraqi Republican Guard and the

SSO. He was

believed to have ordered the army to kill thousands of rebelling Marsh

Arabs and frequently ordered airstrikes on Kurdish and Shi'ite

settlements. He was also believed to have assisted Ali Hassan al-Majid in the 1988 Halabja and Dujail

chemical attacks. He was married once and had three children. His oldest

son, Mustapha Hussein, was killed along with

Uday and Qusay in Mosul.[citation needed]

-

- Raghad Hussein (2 September 1968) is Saddam's oldest

daughter. After the war, Raghad fled to Amman, Jordan

where she received sanctuary from the royal family. She is currently

wanted by the Iraqi Government for

allegedly financing and supporting the insurgency and the now banned

Iraqi Ba'ath Party.[75][76]

The Jordanian royal family refused to hand her over. She married Hussein Kamel al-Majid and has five

children from this marriage.[citation needed]

- Rana Hussein (c. 1969), is Saddam's second daughter. She

like her sister fled to Jordan and has stood up for her father's rights.

She was married to Saddam Kamel and has had four children from

this marriage.

- Hala Hussein (c. 1972), is Saddam's third and youngest

daughter. Very little information is known about her. Her father

arranged for her to marry General Kamal Mustafa Abdallah Sultan

al-Tikriti in 1998. She fled with her children and sisters to Jordan.

The couple have two children.[citation needed]

- Saddam married his second wife, Samira Shahbandar,[77]

in 1986. She was originally the wife of an Iraqi

Airways executive but later became the mistress of Saddam.

Eventually, Saddam forced Samira's husband to divorce her so he could

marry her. [78]

There have been no political issues from this marriage. After the war,

Samira fled to Beirut, Lebanon.

She is believed to have mothered Hussein's sixth son [79].

Members of Hussein's family have denied this.

- Saddam had allegedly married a third wife, Nidal

al-Hamdani, the general manager of the Solar Energy Research Center

in the Council of Scientific Research.[80]

She bore him no children. Her current whereabouts are unknown.[citation needed]

- Wafa

el-Mullah al-Howeish is rumoured to have married Saddam as his

fourth wife in 2002. There is no firm evidence for this marriage. Wafa

is the daughter of Abdul Tawab el-Mullah Howeish, a former minister of

military industry in Iraq and Saddam's last deputy Prime Minister. There

were no children from this marriage. Her current whereabouts are

unknown.[citation needed]

In August 1995, Raghad and her husband Hussein Kamel al-Majid and Rana and

her husband, Saddam Kamel al-Majid, defected to Jordan,

taking their children with them. They returned to Iraq when they

received assurances that Saddam would pardon them. Within three days of

their return in February 1996, both of the Kamel brothers were attacked

and killed in a gunfight with other clan members who considered them

traitors. Saddam had made it clear that although pardoned, they would

lose all status and would not receive any protection.[citation needed]

In August 2003, Saddam's daughters Raghad and Rana received sanctuary

in Amman,

Jordan,

where they are currently staying with their nine children. That month,

they spoke with CNN

and the Arab satellite station Al-Arabiya in Amman. When asked about her

father, Raghad told CNN, "He was a very good father, loving, has a big

heart." Asked if she wanted to give a message to her father, she said:

"I love you and I miss you." Her sister Rana also remarked, "He had so

many feelings and he was very tender with all of us."[81]