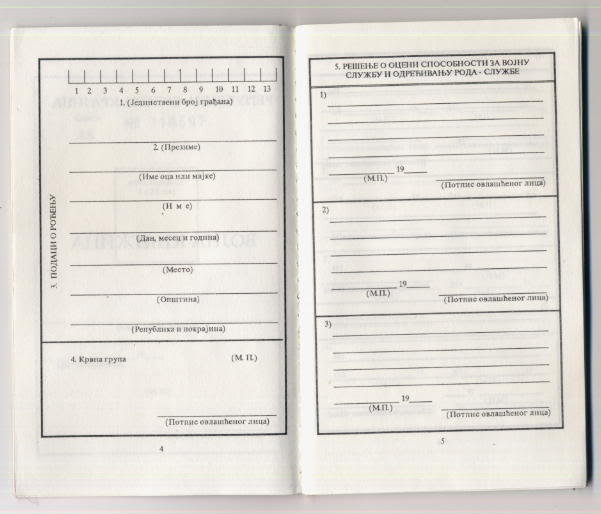

ORIGINAL MILITARY BOOKLET OF THE ARMY OF REPUBLIC SERBIAN - KRAJINA

MILITARY BOOKLET ISSUED IN THE CENTER OF MILITARY COMMAND OF THE REPUBLIC SERBIAN KRAJINA , KNIN .

ISSUED IN 1991/92 WHEN WAR IN CROATIA JUST STARTED.

UNUSED.

RARE AND VERY COLLECTABLE MILITARY ITEM !!!

*****

Republic of Serbian Krajina

The Republic of Serbian Krajina (RSK) (Serbian: Republika Srpska

Krajina, RSK; Република Српска Крајина, РСК; sometimes

translated as Republic of Serb Krajina) was a self-proclaimed Serbian-dominated entity within Croatia.

Established in 1991, it was not recognized internationally. During its

existence, from 1991 to 1994, it was a separatist

government that fought for full independence

for Serbian minority in Croatia from Socialist Croatia and then

from Croatia

once the countries' borders were recognized by foreign states in August

of 1991. The self-governing government

of Krajina had de facto control over central parts of the

territory while control of the outskirts changed with success and

failures of the military activities. In 1992, the Serb Krajina

government signed a demilitarization agreement and removed all of the

heavy artillery that was brought in by Yugoslav People's Army at the start

of the conflict, in exchange the area became a United Nations Protected demilitarized zone. The territory was

legally protected by United Nations Protection Force

and the Military of Serbian Krajina

(without the heavy artillery) until 1995.

Its main portion was overrun by Croatian forces in 1995; a rump

remained in

eastern Slavonia under

United Nations (UN) administration until its peaceful

reincorporation into Croatia in 1998. "Krajina" is an old

Serbian and

Croatian word for "frontier". At this time, a Serb Krajina

has a

Serbian Krajina

Government in exile. The government in exile has no power over the

region in Croatia and has very little or no power over the citizens in diaspora.

Etymology

The name Krajina was adopted from the Military Frontier that was carved out of parts of the crown

lands of Croatia

and Slavonia by Austria between 1553–1578 as a means of defending against

the expansion of the Ottoman Empire. Many Croats, Serbs and Vlachs immigrated from nearby parts of Ottoman

Empire (Ottoman Bosnia and Serbia) into the region and helped bolster

and replenish the numbers of Croats as

well as the garrisoned German troops in the fight against the Ottomans.

The Austrians controlled the Frontier from military headquarters in

Vienna and did not make it a crown

land, though it had some special rights in order to encourage

settlement in an otherwise deserted, war-ravaged territory. The

abolition of the military rule took place between 1869 and 1871. In

order to attract Serbs to be part of Croatia on the 11th of May, 1867

the Sabor solemnly declared that "the Triune Kingdom recognizes the

Serbian/Vlach people living in it as a nation identical and equal with

the Croatian nation." After that, the Military Frontier was

reincorporated in Croatia

in 1881.

Following World War I, the regions formerly part of the

Military Frontier became part of Kingdom of Yugoslavia where it was in the Sava

Banovina with most of old Croatia-Slavonia. Between the two world

wars the Serbs of the Croatian and Slavonian Krajinas, as well as the Bosnian Krajina and other regions west

of Serbia,

organized a notable political party, the Independent Democratic Party

under Svetozar Pribićević. In the new state

there existed much tension between the Croats and Serbs over differing

political visions, with the campaign for Croatian autonomy culminating

in the assassination of their leader Stjepan Radić in the parliament and repression by the Serb

dominated security structures.

Between 1939–1941, in an attempt to resolve the Croat-Serb political

and social antagonism in the first Yugoslavia, an autonomous Banovina of Croatia was created incorporating (amongst

other territories) much of the former Military Frontier as well as parts of Bosnia and Herzegovina. In 1941, the axis

powers invaded Yugoslavia and in the aftermath the Independent State of Croatia

(which included whole of today's Bosnia and Herzegovina and parts of

Serbia (Eastern Syrmia) as well) was declared. The Ustaše

(who were allegedly behind the assassination of the Serbian king of Yugoslavia) were installed by the Germans as rulers

of the new country and promptly pursued a genocidal policy of

persecution of Serbs, Jews and Croats (from opposition groups) leading

to hundreds of thousands being killed. During this period, Croats

coalesced around the ruling authorities or the communist anti-fascist Partisans. Serbs from around the Knin area

tended to join the chetniks, whilst Serbs from the Banija and Slavonia

regions tended to join the Partisans.

At the end of the war, the communist dominated Partisans

prevailed and the region was part of the People's

Republic of Croatia until 7 April 1963, when the federal republic

changed its name to the Socialist Republic of Croatia.

The autonomous political organisations of the region were also

suppressed by Tito (along with others such as the Croatian Spring); however, the Yugoslav constitutions of

1965 and 1974 did give substantial rights to national minorities

including the Serbs in SR Croatia.

The Serbian "Krajina" entity to emerge upon Croatia's declaration of

independence in 1991 would include three kinds of territories:

- a large section of the historical Military Frontier, in areas with a

minority of Serbian population;

- areas such as parts of northern Dalmatia, that were never part of

the Frontier but had a majority or a plurality of Serbian population,

including the self-proclaimed entity's capital, Knin;

- areas that bordered with Serbia and where Serbs are significant

minority (Baranja,

Vukovar).

Large sections of the historical Military Frontier were outside of

the Republic of Serb Krajina and contained a largely Croat population

including much of Lika, the area centred around the city of Bjelovar,

central and south-eastern Slavonia.

Creation

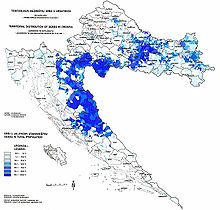

Serb-populated areas in Croatia (according to the 1981 census)

The Serb-populated regions in Croatia were of central concern to the

Serbian popular movement of the late 1980s, led respectively by Slobodan Milošević. The incidents started

in 1988 and turned into full-scale Serbian political rallies in 1989.

The Croatian pro-independence victory in 1990 made matters more tense,

especially since the country's Serbian minority was supported both

politically and militarily by the Yugoslav People's Army, especially

Serbian President Milošević. At the time, Serbs comprised about 12.2% of

Croatia's population: 581,663 people declared themselves Serbs in the

census of 1991.

Serbs became increasingly opposed to the policies of Franjo Tuđman,

elected president of Croatia in April 1990, due to his overt desire for

the creation of an independent Croatia. On May 30, 1990 the Serb Democratic Party of Jovan

Rašković broke all ties to the Croatian parliament. The following June

in Knin, the Serbs-led by the Serb Democratic Party-proclaimed

the creation of the Association of Municipalities of Northern Dalmatia

and Lika. In August 1990, the Serbs began what became known as the Log Revolution, where barricades of logs were placed

across roads throughout the South as an expression of their secession

from Croatia. This effectively cut Croatia in two, separating the

coastal region of Dalmatia from the rest of the country. The Croatian constitution was passed in

December, 1990 putting Serbs in a minority category along with other

ethnic groups such as Italians, Hungarians, and others. Some would later

justify their claim to an independent Serb state by arguing that the

new constitution contradicted the Constitution

of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, because in their

view, Croatia was still legally governed by the Socialist Federal

Republic of Yugoslavia. This was contradicted by the increased signs

of fragmentation within the Yugoslav republics. Croatian leaders

officially insisted on the goal of an independent Croatia as a member of

Yugoslav confederation of independent states.

Serbs in Croatia had established a Serbian National Council in July

1990 to coordinate opposition to Croatian independence. Their position

was that if Croatia could secede from Yugoslavia, then the Serbs could

secede from Croatia. Milan

Babić, a dentist from the southern town of Knin, was

elected president. At his ICTY trial in 2004, he claimed that

"during the events [of 1990-1992], and in particular at the beginning

of his political career, he was strongly influenced and misled by

Serbian propaganda, which repeatedly referred to the imminent threat of a

Croatian genocide perpetrated on the Serbs in Croatia, thus creating an

atmosphere of hatred and fear of Croats."[3]

The rebel Croatian Serbs established a number of paramilitary

militias under the leadership of Milan Martić, the police chief in Knin.

An

ID issued by the Republic of Serbian

Krajina government in 1997.

In August 1990, a referendum was held in the Krajina on the question

of Serb "sovereignty and autonomy" in Croatia. The resolution was

confined exclusively to Serbs so it passed by a majority of 99.7%. As

expected, it was declared illegal and invalid by the Croatian

government, who stated that Serbs had no constitutional right to break

away from Croatian legal territory.

Babić's administration announced the creation of a Serbian

Autonomous Oblast of Krajina (or SAO Krajina) on 21 December

1990. On 16 March 1991 another referendum was held which asked "Are you

in favour of the SAO Krajina joining the Republic of Serbia and staying

in Yugoslavia with Serbia, Montenegro and others who wish to preserve

Yugoslavia?". With 99.8% voting in favour, the referendum was approved

and the Krajina assembly declared that "the territory of the SAO Krajina

is a constitutive part of the unified state territory of the Republic

of Serbia".[4]

On 1 April 1991, it declared that it would secede from Croatia. Other

Serb-dominated communities in eastern Croatia announced that they would

also join SAO Krajina and ceased paying taxes to the Zagreb

government, and began implementing its own currency system, army

regiments, and postal service.

Croatia held a referendum on independence on 19 May 1991, in which

the electorate—minus many Serbs, who chose to boycott it—voted

overwhelmingly for independence with the option of confederate union

with other Yugoslav states. On 25 June 1991, Croatia and Slovenia both

declared their independence from Yugoslavia. As the JNA attempted

unsuccessfully to suppress Slovenia's independence in the short Slovenian War, clashes between rebelled Croatian

Serbs and Croatian security forces broke out almost immediately,

leaving dozens dead on both sides. Serbs calling themselves Chetniks[5]

were supported by the remnants of the JNA (whose members were now only

from Serbia and Montenegro), which provided them military arms. Many

Croatians fled their homes in fear, or were forced out by the rebel

Serbs. The European Union and United Nations attempted to broker ceasefires and peace

settlements, but all to no avail.

Around August 1991, the leadership of the Serbian Krajina, and that

of Serbia, allegedly agreed to embark on a campaign which the ICTY

prosecutors described as a "joint criminal enterprise" whose purpose

"was the forcible removal of the majority of the Croat and other

non-Serb population from approximately one-third of the territory of the

Republic of Croatia, an area he planned to become part of a new

Serb-dominated state."[6]

The leaders are documented to have included Milan Babić, and other

rebelled Croatian Serbs' figures such as Milan Martić, the Serbian

militia leader Vojislav Šešelj and Yugoslav Army commanders

including General Ratko Mladić, who was at the time the commander of JNA

forces in Croatia.

According to testimony given by Babić in his subsequent war crimes

trial, during the summer of 1991 the Serbian secret police—under

Milošević's command—set up "a parallel structure of state security and

the police of Krajina and units commanded by the state security of

Serbia". Shadowy groups of paramilitaries with names such as the "Vukovi

sa Vucjaka" ("Wolves from Vucjak") and the "Beli Orlovi" ("White

Eagles"), funded by the Serbian secret

police, were also a key component of this structure.[7]

A wider-scale war was launched in August 1991. Over the following

months, a large area of territory, amounting to a third of Croatia, was

controlled by the rebel Serbs. The Croatian population suffered heavily,

fleeing or evicted with numerous killings, leading to ethnic cleansing.[8]

The bulk of the fighting occurred between August and December 1991 when

approximately 80,000 Croats were expelled (and some were killed).[9]

Many more died and or were displaced in fighting in eastern Slavonia

(this territory along the Croatian/Serbian border was not part of the

Krajina, and it was the JNA that was the principal actor in that part of

the conflict). The Gospić massacre was one of the war crimes committed by

Croatian military against the Serbian civilians.

On 19 December 1991, the SAO Krajina proclaimed itself the Republic

of Serbian Krajina. On 26 February 1992, the SAO Western Slavonia and

SAO Slavonia, Baranja and Western Srem were added to the RSK, which

initially had only encompassed the territories within the SAO Krajina.

The Serb Army of Krajina (Српска Војска Крајине / Srpska

Vojska Krajine ; abbreviated СВК / SVK) (or the Republic of

Serbian Krajina Army) was officially formed on 19 March 1992. The

RSK occupied an area of some 17,028 km² at its greatest extent. Croatia

then was beginning to form an army and their main defenders, the local

police, were overpowered by the JNA military who supported rebelled

Croatian Serbs. The RSK was located entirely inland, but they soon

started advancing deeper into Croatian territory.[8]

They shelled the Croatian coastal town of Zadar

killing over 80 people in nearby areas and damaging the Maslenica bridge

that connected northern and southern Croatia. They also tried to

overtake Šibenik, but the defenders successfully repelled the

attack by JNA. The main city theatre was also bombed by JNA forces.[10]

The city of Vukovar, however, was completely devastated by JNA

attacks.[11]

The city of Vukovar that warded off JNA attacks for months eventually

fell. 2,000 defenders of Vukovar and civilians were killed, 800 went

missing and 22,000 were forced into exile.[12][13]

The wounded were taken from Vukovar Hospital to Ovcara near Vukovar

where they were executed.[14]

1992 ceasefire

War in former Yugoslavia, 1993

A ceasefire agreement was signed by Presidents Tuđman and Milošević

in January 1992, paving the way for the implementation of a United

Nations peace plan put forward by Cyrus

Vance. Under the Vance

Plan, four United Nations Protected Areas (UNPAs) were established

in Croatian territory which was claimed by RSK. The Vance Plan called

for the withdrawal of the JNA from Croatia and for the return of

refugees to their homes in the UNPAs. The JNA officially withdrew from

Croatia in May 1992 but much of its weaponry and many of its personnel

remained in the Serb-held areas and were turned over to the RSK's

security forces. Refugees were not allowed to return to their homes and

many of the remaining Croats and other nationalities left in the RSK

were expelled or killed in the following months.[11][15]

On 21 February 1992, the creation of the United Nations Protection Force

(UNPROFOR) was authorised by the UN Security Council for an

initial period of a year, to provide security to the UNPAs.

The agreement effectively froze the front lines for the next three

years. Croatia and the RSK had effectively fought each other to a

standstill. The Republic of Serbian Krajina was not recognised de jure

by any other country or international organisation. Nevertheless it

gained support from Serbia's allies, Greece, Russia,

and Romania.

With the creation of new Croatian counties on 30 December 1992, the Croatian

government also set aside two autonomous regions (kotar) for

ethnic Serbs in the areas of Krajina. However, Serbs considered this too

late, as it was not the amount of autonomy they wanted, and by now they

had declared de facto independence.

UNPROFOR was deployed throughout the region to maintain the

ceasefire, although in practice its light armament and restricted rules

of engagement meant that it was little more than an observer force. It

proved wholly unable to ensure that refugees returned to the RSK.

Indeed, the rebel Croatian Serb authorities continued to make efforts to

ensure that they could never return, destroying villages and

cultural and religious monuments to erase the previous existence of the

Croatian inhabitants of the Krajina.[11]

Milan Babić later testified that this policy was driven from Belgrade

through the Serbian secret police—and ultimately Milošević—who he

claimed were in control of all the administrative institutions and armed

forces in the Krajina.[16]

This would certainly explain why the Yugoslav National Army took the

side of the rebelled Croatian Serbs in spite of its claims to be acting

as a "peacekeeping" force. Milošević denied this, claiming that Babić

had made it up "out of fear".

Decline

The partial implementation of the Vance Plan drove a wedge between

the governments of the RSK and Serbia, the RSK's principal backer and

supplier of fuel, arms and money. Milan Babić strongly opposed the Vance

Plan but was overruled by the RSK's assembly.[11]

On 26 February 1992, Babić was deposed and replaced as President of

the RSK by Goran Hadžić, a Milošević loyalist. Babić

remained involved in RSK politics but as a considerably weaker figure.

The position of the RSK eroded steadily over the following three

years. On the surface, the RSK had all the trappings of a state: army,

parliament, president, government and ministries, currency and stamps.

However its economy was wholly dependent on support from the rump

Yugoslavia, which had the effect of importing that country's hyperinflation.

1992 RSK 5,000,000 Dinar banknote

In July 1992 the RSK issued its own currency, the Krajina

dinar (HRKR), in parallel with the Yugoslav dinar. This was followed by the "October dinar"

(HRKO), first issued on 1 October 1993 and equal to 1,000,000 Reformed

Dinar, and the "1994 dinar", first issued on 1 January 1994, and equal

to 1,000,000,000 October dinar.

The economic situation soon became disastrous. By 1994, only 36,000

of the RSK's 430,000 citizens were employed. The war had severed the

RSK's trade links with the rest of Croatia, leaving its few industries

idle. With few natural resources of its own it had to import most of the

goods and fuel it required. Agriculture was devastated, and operated at

little more than a subsistence level.[2]

Professionals went to Serbia or elsewhere to escape the republic's

economic hardships. To make matters worse, the RSK's government was

grossly corrupt and the region became a haven for black marketeering and

other criminal activity. It was clear by the mid-1990s that without a

peace deal or support from Yugoslavia the RSK was not economically

viable.[17]

This was especially evident in Belgrade, where the RSK had become an

unwanted economic and political burden for Milošević. Much to his

frustration, the rebel Croatian Serbs rebuffed his government's demands

to settle the conflict.[11]

The RSK's weakness also adversely affected its armed forces, the Vojska Srpske Krajine (VSK).

Since the 1992 ceasefire agreement, Croatia had spent heavily on

importing weapons and training its armed forces with assistance from

American contractors. In contrast, the VSK had grown steadily weaker,

with its soldiers poorly motivated, trained and equipped.[11][18]

There were only about 55,000 of them to cover a front of some 600 km in

Croatia plus 100 km along the border with the Bihać

pocket in Bosnia. With 16,000 stationed in eastern Slavonia, only about

39,000 were left to defend the main part of the RSK. Overall, only

30,000 were capable of full mobilization, yet they faced a far stronger

Croatian army. Also, political divisions between Hadžić and Babić

occasionally led to physical and sometimes even armed confrontations

between their supporters; Babić himself was assaulted and beaten in an

incident in Benkovac.[19][20]

In January 1993 the revitalized Croatian army attacked the Serbian

positions around Maslenica in southern Croatia which curtailed

their access to the sea via Novigrad. In a second offensive in

September 1993 the Croatian army overran the Medak pocket in the southern Krajina in a push

to regain Serb-held Croatian territory. This action was halted by

international diplomacy but although the rebel Croatian Serbs brought

reinforcements forward fairly quickly, the strength of the Croatian

forces proved superior. Hadžić sent an urgent request to Belgrade for

reinforcements, arms and equipment. In response, around 4,000

paramilitaries under the command of Vojislav Šešelj (the White Eagles) and "Arkan" (the Serb Volunteer Guard) arrived to bolster the VSK.

They found the RSK government and military in a chaotic state.[citation needed]

Operation Storm

August 4th order by the RSK Supreme Defence Council ordering evacuation

of civilians from towns along the front line in the Knin area.

Following the rejection by both sides of the Z-4 plan

for reintegration, the RSK's end came in 1995, when Croatian forces

gained control of SAO Western Slavonia in Operation Flash (May) followed by the biggest part of

occupied Croatia in Operation Storm (August). The Krajina Serb Supreme Defence

Council met under president Milan Martić to discuss the situation. A decision was

reached at 16:45 to "start evacuating the population unfit for military

service from the municipalities of Knin, Benkovac,

Obrovac,

Drniš

and Gračac."

The RSK was disbanded and most of the Serb population fled.[11][21]

Only 5,000 to 6,000 people remained, mostly the elderly.[22]

Historian Ivo Goldstein wrote, "The reasons for the Serb

exodus are complex. Some had to leave because the Serb army forced them

to, while others feared the revenge of the Croatian army and whose

homes they had mostly looted".[22]

Most of the refugees ended in Serbia, Bosnia and eastern Slavonia.

Some of those who remained were murdered, tortured and forcibly expelled

by the Croatian Army and police.[21]

Croatia celebrates this victory on 5 August as Victory Day. There was also widespread

arson committed by the Croatian soldiers, judged by the ICTY to be an

action organised to prevent the Serbs from returning.[23]

A number of Croatian army officers (such as general Ante

Gotovina) were indicted by the ICTY in the Hague for command

responsibility for the atrocities committed by Croatian soldiers against

the civilian Serb population.[23]

The parts of the former RSK in eastern Croatia (along the Danube)

remained in place as the Republic

of Eastern Slavonia, Baranja and Western Syrmia (previously the SAO Eastern

Slavonia, Baranja and Western Syrmia, or sometimes called Sremsko-Baranjska

Oblast). The national and local authorities signed the Erdut

Agreement in 1995, sponsored by the United Nations, that set up a

transitional period during which the UNTAES peacekeepers would oversee a peaceful

reintegration of this territory into Croatia. This process was completed

in 1998. After the peaceful reintegration Croatian islands of Šarengrad and Vukovar remained under Serbian military control. In 2004,

Serbian military was withdrawn from the islands and replaced with

Serbian police. Thus, the islands remain an open question.[24]

Demographics

According to the indictment of prosecutor Carla Del Ponte against Slobodan Milošević at the International

Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), the Croat and

non-Serb population from the 1991 census was approximately as follows:[25]

Thus Serbs comprised 67%, 60% and 32% of the population of SAO

Krajina, SAO Western Slavonia, and SAO SBWS respectively in 1991.

According to data set forth at the meeting of the Government of the

RSK in July 1992, its ethnic composition was 88% Serbs, 7% Croats, 5%

others.[19]

War crimes

[edit] Croats

Several Croatian military leaders were indicted by the ICTY of various war crimes, including

persecution, murder, plunder and planning the ethnic cleansing.

- Ante Gotovina is charged with ranking responsibility for

the murder of about 150 Serbs and persecution and deportation of

thousands.[26]

- Mladen Markač and Ivan

Čermak are charged with planning, establishing, implementing and/or

participating "in a joint criminal enterprise, the common purpose and

objectives of which were the permanent removal of the Serb population

from the Krajina region, by force, fear or threat of force, persecution,

forced displacement, transfer and deportation, appropriation and

destruction of property and other means, which constituted or involved

the commission of crimes".[27][28]

Serbs

Several members of the RSK leadership ended up being indicted of war

crimes by the ICTY.[29]

- Milan Babić, president of the RSK, was sentenced to 13 years

for persecution on political, racial and religious grounds as a crime

against humanity, to which he pleaded guilty. He was found dead in his ICTY prison cell on 6 March 2006, having

apparently committed suicide.[30]

- Milan Martić, president of the RSK, was

sentenced to 35 years in prison for multiple war crimes, including

persecution, torture, deportation, and attacks on civilians.[31]

- Goran Hadžić is still at large as of August

2009[update].[32]

- Jovica Stanišić, head of Serbia's State

Security Service, and Franko Simatović, a commander of the State Security

Service, are indicted on several accounts of persecution as a crime

against humanity and murder.[33]

- Momčilo Perišić, Chief of the General Staff

of the Yugoslav Army, is awaiting trial on counts of murder.[34]

- Veselin Šljivančanin, Lieutenant

Colonel of the Yugoslav Army, convicted of his role in the Vukovar massacre.[35]

Legal status

During its existence, this entity did not achieve international

recognition. In January 1992, the Badinter commission concluded that Yugoslavia was "in

dissolution" and that the republics - including Croatia - should be

recognized as independent states when they asked so.[36][37]

They also assigned these republics territorial integrity. For most of

the world this was a reason to recognize Croatia. However, Serbia did

not accept the conclusions of the commission in that period and

recognized Croatia only after Croatian military actions (Oluja and

Bljesak) and Dayton agreement.

Government in exile

There exists a self-proclaimed government in exile for the Republic

of Serbian Krajina. This government existed for a short time period

after Operation Storm, but was reconstituted in 2005. This

self-proclaimed government has changed the official name of the Republic

of Serbian Krajina to Republic of Serb-Krajina.

On 12 September 2008, government of Republic of Serb-Krajina in exile

recognized

Abkhazia and South Ossetia[38]..

*****

PLEASE READ CAREFULY MY PAYMENT INSTRUCTION BEFORE YOU BID.

PLEASE DO NOT BID IF YOU DO NOT ACCEPT ANY OF MY PAYMENT TERMS !!!

********************